Medi Services

To carry out a chest compression:

When you call for an ambulance, telephone systems now exist that can give basic life-saving instructions, including advice about CPR. These are now common and are easily accessible with mobile phones.

If you’ve been trained in CPR, including rescue breaths, and feel confident using your skills, you should give chest compressions with rescue breaths. If you're not completely confident, attempt hands-only CPR instead (see above).

If the child is under one year old:

If the child is over one year old:

If you think there may have been an injury to the neck, tilt the head carefully, a small amount at a time, until the airway is open. Opening the airway takes priority over a possible neck injury, however.

Keeping the airway open, look, listen and feel for normal breathing by putting your face close to your child's face and looking along their chest.

Look, listen and feel for no more than 10 seconds before deciding that they're not breathing. Gasping breaths should not be considered to be normal breathing.

Rescue breaths for a baby under one year

Rescue breaths for a child over one year

If you have difficulty achieving effective breathing in your child, the airway may be obstructed.

Look for signs of life. These include any movement, coughing, or normal breathing – not abnormal gasps or infrequent, irregular breaths.

Signs of life present

If there are definite signs of life:

No signs of life present

If there are no signs of life:

Although the rate of compressions will be 100-120 a minute, the actual number delivered will be fewer because of the pauses to give breaths.

The best method for compression varies slightly between infants and children.

Chest compression in babies less than one year

Chest compression in children over one year

If nobody responded to your shout for help at the beginning and you're alone, continue resuscitation for about one minute before trying to get help – for example, by dialling 999 on a mobile phone.

| 1. Dangers? Check for dangers. Consider why the person appears to be in trouble – is there gas present or have they been electrocuted? Might they be drunk or drug-affected and consequently a hazard to you? Approach with care and do not put yourself in danger. If the person is in a hazardous area (such as on a road), it is okay to move them as gently as possible to protect both your and their safety. |

| 2. Response? Look for a response. Is the victim conscious? Gently shake them and shout at them, as if you are trying to wake them up. If there is no response, get help. |

| 3. Send for help. Dial triple zero (000) – ask for an ambulance. |

| 4. Open airway. Check the airway. It is reasonable to gently roll the person on their back if you need to. Gently tilt their head back, open their mouth and look inside. If fluid and foreign matter is present, gently roll them onto their side. Tilt their head back, open their mouth and very quickly remove any foreign matter (for example, chewing gum, false teeth, vomit). It is important not to spend much time doing this, as performing CPR is the priority. Chest compressions can help to push foreign material back out of the upper airway. |

| 5. Normal breathing? Check for breathing – look, listen and feel for signs of breathing. If the person is breathing normally, roll them onto their side. If they are not breathing, or not breathing normally, go to step 6. The person in cardiac arrest may make occasional grunting or snoring attempts to breathe and this is not normal breathing. If unsure of whether a person is breathing normally, start CPR as per step six. |

| 6. Start CPR Cardiac compressions:

|

| Establishing compressions is the clear priority. If a rescuer cannot coordinate the breathing or finds it too time-consuming or too unpleasant, effective chest compressions alone will still be of benefit. It is important not to avoid all resuscitation efforts because of the mouth-to-mouth component. 7. Mouth-to-mouth. If the person is not breathing normally, make sure they are lying on their back on a firm surface and:

|

8. Attach automated external defibrillator (AED) as soon as one becomes available.

|

If you haven’t received formal training in CPR, theAmerican Heart Association recommends performing hands-only CPR. This helps increase blood circulation to prevent death. First, call 911. After calling 911, push hard on the center of the person’s chest. Repeat this in a fast motion. Many people are afraid to perform hands-only CPR, but the fact is that it’s worse to take no action.

Full CPR has two more steps. These are the cornerstones of CPR:

If the person responds, either by speaking, beginning to move, or breathing normally, you can stop performing CPR.

It is also important to know that techniques vary between CPR procedures for adults, children, and infants. Never perform adult CPR on children.

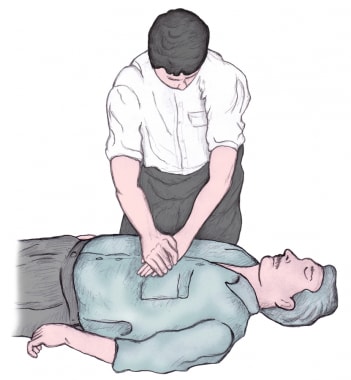

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) consists of the use of chest compressions and artificial ventilation to maintain circulatory flow and oxygenation during cardiac arrest (see the images below). Although survival rates and neurologic outcomes are poor for patients with cardiac arrest, early appropriate resuscitation—involving early defibrillation—and appropriate implementation of post–cardiac arrest care lead to improved survival and neurologic outcomes.

Delivery of chest compressions. Note the overlapping hands placed on the center of the sternum, with the rescuer's arms extended. Chest compressions are to be delivered at a rate of at least 100 compressions per minute.

Delivery of chest compressions. Note the overlapping hands placed on the center of the sternum, with the rescuer's arms extended. Chest compressions are to be delivered at a rate of at least 100 compressions per minute.CPR should be performed immediately on any person who has become unconscious and is found to be pulseless. Assessment of cardiac electrical activity via rapid “rhythm strip” recording can provide a more detailed analysis of the type of cardiac arrest, as well as indicate additional treatment options.

Loss of effective cardiac activity is generally due to the spontaneous initiation of a nonperfusing arrhythmia, sometimes referred to as a malignant arrhythmia. The most common nonperfusing arrhythmias include the following:

CPR should be started before the rhythm is identified and should be continued while the defibrillator is being applied and charged. Additionally, CPR should be resumed immediately after a defibrillatory shock until a pulsatile state is established.

The only absolute contraindication to CPR is a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order or other advanced directive indicating a person’s desire to not be resuscitated in the event of cardiac arrest. A relative contraindication to performing CPR is if a clinician justifiably feels that the intervention would be medically futile.

CPR, in its most basic form, can be performed anywhere without the need for specialized equipment. Universal precautions (ie, gloves, mask, gown) should be taken. However, CPR is delivered without such protections in the vast majority of patients who are resuscitated in the out-of-hospital setting, and no cases of disease transmission via CPR delivery have been confirmed. Some hospitals and EMS systems employ devices to provide mechanical chest compressions. A cardiac defibrillator provides an electrical shock to the heart via 2 electrodes placed on the patient’s torso and may restore the heart into a normal perfusing rhythm.

In its full, standard form, CPR comprises the following 3 steps, performed in order:

For lay rescuers, compression-only CPR (COCPR) is recommended.

Positioning for CPR is as follows:

For an unconscious adult, CPR is initiated as follows:

Chest compression

The provider should do the following:

Ventilation

If the patient is not breathing, 2 ventilations are given via the provider’s mouth or abag-valve-mask (BVM). If available, a barrier device (pocket mask or face shield) should be used.

To perform the BVM or invasive airway technique, the provider does the following:

To perform the mouth-to-mouth technique, the provider does the following:

Complications of CPR include the following:

In the in-hospital setting or when a paramedic or other advanced provider is present, ACLS guidelines call for a more robust approach to treatment of cardiac arrest, including the following:

Emergency cardiac treatments no longer recommended include the following:

For patients with cardiac arrest, survival rates and neurologic outcomes are poor, though early appropriate resuscitation, involving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), early defibrillation, and appropriate implementation of post–cardiac arrest care, leads to improved survival and neurologic outcomes. Targeted education and training regarding treatment of cardiac arrest directed at emergency medical services (EMS) professionals as well as the public has significantly increased cardiac arrest survival rates.[1]

CPR consists of the use of chest compressions and artificial ventilation to maintain circulatory flow and oxygenation during cardiac arrest. A variation of CPR known as “hands-only” or “compression-only” CPR (COCPR) consists solely of chest compressions. This variant therapy is receiving growing attention as an option for lay providers (that is, nonmedical witnesses to cardiac arrest events).

The relative merits of standard CPR and COCPR continue to be widely debated. An observational study involving more than 40,000 patients concluded that standard CPR was associated with increased survival and more favorable neurologic outcomes than COCPR was.[2] However, other studies have shown opposite results, and it is currently accepted that COCPR is superior to standard CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Several large randomized controlled and prospective cohort trials, as well as one meta-analysis, demonstrated that bystander-performed COCPR leads to improved survival in adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, in comparison with standard CPR.[3, 4, 5] Differences between these results may be attributable to a subgroup of younger patients arresting from noncardiac causes, who clearly demonstrate better outcomes with conventional CPR.[2]

The 2010 revisions to the American Heart Association (AHA) CPR guidelines state that untrained bystanders should perform COCPR in place of standard CPR or no CPR (see American Heart Association CPR Guidelines).[6]

Of the more than 300,000 cardiac arrests that occur annually in the United States, survival rates are typically lower than 10% for out-of-hospital events and lower than 20% for in-hospital events.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11] A study by Akahane et al suggested that survival rates may be higher in men but that neurologic outcomes may be better in women of younger age, though the reasons for such sex differences are unclear.[12]

Additionally, studies have shown that survival falls by 10-15% for each minute of cardiac arrest without CPR delivery.[13, 14] Bystander CPR initiated within minutes of the onset of arrest has been shown to improve survival rates 2- to 3-fold, as well as improve neurologic outcomes at 1 month.[15, 16]

It has also been demonstrated that out-of hospital cardiac arrests occurring in public areas are more likely to be associated with initial ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) and have better survival rates than arrests occurring at home.[17]

This article focuses on CPR, which is just one aspect of resuscitation care. Other interventions, such as the administration of pharmacologic agents, cardiac defibrillation, invasive airway procedures, post–cardiac arrest therapeutic hypothermia,[18, 19, 20, 21, 22] the use of echocardiography in resuscitation,[23] and various diagnostic maneuvers,[24, 25] are beyond the scope of this article. For more information, see the Resuscitation Resource Center; for specific information on the resuscitation of neonates, see Neonatal Resuscitation.

In 2010, the Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee (ECC) of the AHA released the Association’s newest set of guidelines for CPR. Changes for 2010 include the following[24, 26] :

Several studies that looked at the quality of CPR being performed in hospitals and by EMS systems found that providers often did not perform CPR up to the standards of the ECC guidelines.[28, 29, 30, 31] Specifically, they found that providers were often deficient in both rate and depth of chest compressions and often provided ventilations at too high a rate. Other studies demonstrated the impact of inadequate rate and depth on survival.[32]

The 2010 AHA guidelines state that untrained bystanders should perform COCPR (previous AHA guidelines did not address untrained bystanders separately).[6]

Several studies concluded that stopping compressions in order to give ventilations may be detrimental to the patient’s outcome.[33, 34, 35] While a bystander halts compressions to give 2 breaths, blood flow also stops, and this cessation of blood flow leads to a quick drop in the blood pressure that had been built up during the previous set of compressions.[36]

Note these guidelines were updated again in 2015 and are available at 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines for CPR & ECC.

CPR should be performed immediately on any person who has become unconscious and is found to be pulseless. Assessment of cardiac electrical activity via rapid “rhythm strip” recording can provide a more detailed analysis of the type of cardiac arrest, as well as indicate additional treatment options.

Loss of effective cardiac activity is generally due to the spontaneous initiation of a nonperfusing arrhythmia, sometimes referred to as a malignant arrhythmia. The most common nonperfusing arrhythmias include the following:

Although prompt defibrillation has been shown to improve survival for VF and pulseless VT rhythms,[37] CPR should be started before the rhythm is identified and should be continued while the defibrillator is being applied and charged. Additionally, CPR should be resumed immediately after a defibrillatory shock until a pulsatile state is established. This is supported by studies showing that “preshock pauses” in CPR result in lower rates of defibrillation success and patient recovery.[32]

In a study involving out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Seattle, 84% of patients regained a pulse when defibrillated during VF.[30] Defibrillation is generally most effective the faster it is deployed.

The American College of Surgeons, the American College of Emergency Physicians, the National Association of EMS Physicians, and the American Academy of Pediatrics have issued guidelines on the withholding or termination of resuscitation in pediatric out-of-hospital traumatic cardiopulmonary arrest.[38]Recommendations include the following:

The only absolute contraindication to CPR is a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order or other advanced directive indicating a person’s desire to not be resuscitated in the event of cardiac arrest.

A relative contraindication to performing CPR may arise if a clinician justifiably feels that the intervention would be medically futile, although this is clearly a complex issue that is an active area of research.[39, 40]