Signs and symptoms

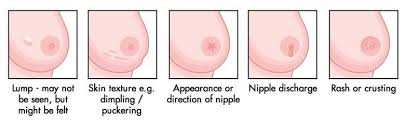

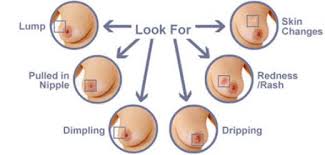

Breast cancer showing an inverted nipple, lump and skin dimpling. The first noticeable symptom of breast cancer is typically a lump that feels different from the rest of the breast tissue. More than 80% of breast cancer cases are discovered when the woman feels a lump.[15] The earliest breast cancers are detected by a mammogram.[16] Lumps found in lymph nodes located in the armpits[15]can also indicate breast cancer.

Indications of breast cancer other than a lump may include thickening different from the other breast tissue, one breast becoming larger or lower, a nipple changing position or shape or becoming inverted, skin puckering or dimpling, a rash on or around a nipple, discharge from nipple/s, constant pain in part of the breast or armpit, and swelling beneath the armpit or around the collarbone.[17] Pain ("mastodynia") is an unreliable tool in determining the presence or absence of breast cancer, but may be indicative of other breast health issues.[15][16][18]

Inflammatory breast cancer is a particular type of breast cancer which can pose a substantial diagnostic challenge. Symptoms may resemble a breast inflammation and may include itching, pain, swelling, nipple inversion, warmth and redness throughout the breast, as well as an orange-peel texture to the skin referred to as peau d'orange;[15] as inflammatory breast cancer doesn't show as a lump there's sometimes a delay in diagnosis.

Another reported symptom complex of breast cancer is Paget's disease of the breast. This syndrome presents as skin changes resembling eczema, such as redness, discoloration, or mild flaking of the nipple skin. As Paget's disease of the breast advances, symptoms may include tingling, itching, increased sensitivity, burning, and pain. There may also be discharge from the nipple. Approximately half of women diagnosed with Paget's disease of the breast also have a lump in the breast.[19]

In rare cases, what initially appears as a fibroadenoma (hard, movable non-cancerous lump) could in fact be a phyllodes tumor. Phyllodes tumors are formed within the stroma (connective tissue) of the breast and contain glandular as well as stromal tissue. Phyllodes tumors are not staged in the usual sense; they are classified on the basis of their appearance under the microscope as benign, borderline, or malignant.[20]

Occasionally, breast cancer presents as metastatic disease—that is, cancer that has spread beyond the original organ. The symptoms caused by metastatic breast cancer will depend on the location of metastasis. Common sites of metastasis include bone, liver, lung and brain.[21] Unexplained weight loss can occasionally signal breast cancer, as can symptoms of fevers or chills. Bone or joint pains can sometimes be manifestations of metastatic breast cancer, as can jaundice or neurological symptoms. These symptoms are called non-specific, meaning they could be manifestations of many other illnesses.[22]

Most symptoms of breast disorders, including most lumps, do not turn out to represent underlying breast cancer. Fewer than 20% of lumps, for example, are cancerous,[23] and benign breast diseases such as mastitis and fibroadenoma of the breast are more common causes of breast disorder symptoms. Nevertheless, the appearance of a new symptom should be taken seriously by both patients and their doctors, because of the possibility of an underlying breast cancer at almost any age.[24]

Risk factors

Risk factors can be divided into two categories:

- modifiable risk factors (things that people can change themselves, such as consumption of alcoholic beverages), and

- fixed risk factors (things that cannot be changed, such as age and biological sex).[25]

The primary risk factors for breast cancer are female sex and older age.[26] Other potential risk factors include: genetics,[27] lack of childbearing or lack of breastfeeding,[28] higher levels of certain hormones,[29][30] certain dietary patterns, and obesity. Recent studies have indicated that exposure to light pollution is a risk factor for the development of breast cancer.[31]

Lifestyle

Smoking tobacco appears to increase the risk of breast cancer, with the greater the amount smoked and the earlier in life that smoking began, the higher the risk.[32] In those who are long-term smokers, the risk is increased 35% to 50%.[32] A lack of physical activity has been linked to ~10% of cases.[33] Sitting regularly for prolonged periods is associated with higher mortality from breast cancer. The risk is not negated by regular exercise, though it is lowered.[34]

There is an association between use of hormonal birth control and the development of premenopausal breast cancer,[25][35] but whether oral contraceptives use may actually cause premenopausal breast cancer is a matter of debate.[36] If there is indeed a link, the absolute effect is small.[36][37] Additionally, it is not clear if the association exists with newer hormonal birth controls.[37] In those with mutations in the breast cancer susceptibility genes BRCA1 or BRCA2, or who have a family history of breast cancer, use of modern oral contraceptives does not appear to affect the risk of breast cancer.[38][39]

The association between breast feeding and breast cancer has not been clearly determined; some studies have found support for an association while others have not.[40] In the 1980s, the abortion–breast cancer hypothesis posited that induced abortion increased the risk of developing breast cancer.[41] This hypothesis was the subject of extensive scientific inquiry, which concluded that neithermiscarriages nor abortions are associated with a heightened risk for breast cancer.[42]

A number of dietary factors have been linked to the risk for breast cancer. Dietary factors which may increase risk include a high fat diet,[43] high alcohol intake,[44] and obesity related high cholesterollevels.[45][46] Dietary iodine deficiency may also play a role.[47] Evidence for fiber is unclear. A 2015 review found that studies trying to link fiber intake with breast cancer produced mixed results.[48] In 2016 a tentative association between low fiber intake during adolescence and breast cancer was observed.[49]

Other risk factors include radiation,[50] and shift-work.[51] A number of chemicals have also been linked including: polychlorinated biphenyls, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, organic solvents[52] Although the radiation from mammography is a low dose, it is estimated that yearly screening from 40 to 80 years of age will cause approximately 225 cases of fatal breast cancer per million women screened.[53]

Genetics

Some genetic susceptibility may play a minor role in most cases.[54] Overall, however, genetics is believed to be the primary cause of 5–10% of all cases.[55] Women whose mother was diagnosed before 50 have an increased risk of 1.7 and those whose mother was diagnosed at age 50 or after has an increased risk of 1.4.[56] In those with zero, one or two affected relatives, the risk of breast cancer before the age of 80 is 7.8%, 13.3%, and 21.1% with a subsequent mortality from the disease of 2.3%, 4.2%, and 7.6% respectively.[57] In those with a first degree relative with the disease the risk of breast cancer between the age of 40 and 50 is double that of the general population.[58]

In less than 5% of cases, genetics plays a more significant role by causing a hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome.[54] This includes those who carry the BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene mutation.[54] These mutations account for up to 90% of the total genetic influence with a risk of breast cancer of 60–80% in those affected.[55] Other significant mutations include: p53 (Li–Fraumeni syndrome), PTEN(Cowden syndrome), and STK11 (Peutz–Jeghers syndrome), CHEK2, ATM, BRIP1, and PALB2.[55] In 2012, researchers said that there are four genetically distinct types of the breast cancer and that in each type, hallmark genetic changes lead to many cancers.[59]

Medical conditions

Breast changes like atypical ductal hyperplasia[60] and lobular carcinoma in situ,found in benign breast conditions such as fibrocystic breast changes, are correlated with an increased breast cancer risk. Diabetes mellitus might also increase the risk of breast cancer.[64]

Pathophysiology

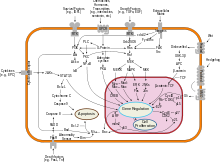

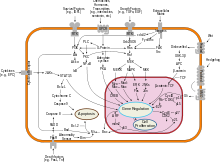

Overview of signal transduction pathways involved in apoptosis. Mutations leading to loss of apoptosis can lead to tumorigenesis. Breast cancer, like other cancers, occurs because of an interaction between an environmental (external) factor and a genetically susceptible host. Normal cells divide as many times as needed and stop. They attach to other cells and stay in place in tissues. Cells become cancerous when they lose their ability to stop dividing, to attach to other cells, to stay where they belong, and to die at the proper time.

Normal cells will commit cell suicide (apoptosis) when they are no longer needed. Until then, they are protected from cell suicide by several protein clusters and pathways. One of the protective pathways is the PI3K/AKT pathway; another is the RAS/MEK/ERK pathway. Sometimes the genes along these protective pathways are mutated in a way that turns them permanently "on", rendering the cell incapable of committing suicide when it is no longer needed. This is one of the steps that causes cancer in combination with other mutations. Normally, the PTEN protein turns off the PI3K/AKT pathway when the cell is ready for cell suicide. In some breast cancers, the gene for the PTEN protein is mutated, so the PI3K/AKT pathway is stuck in the "on" position, and the cancer cell does not commit suicide.[65]

Mutations that can lead to breast cancer have been experimentally linked to estrogen exposure.[66]

Abnormal growth factor signaling in the interaction between stromal cells and epithelial cells can facilitate malignant cell growth.[67][68] In breast adipose tissue, overexpression of leptin leads to increased cell proliferation and cancer.[69]

In the United States, 10 to 20 percent of people with breast cancer and people with ovarian cancer have a first- or second-degree relative with one of these diseases. The familial tendency to develop these cancers is called hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndrome. The best known of these, the BRCA mutations, confer a lifetime risk of breast cancer of between 60 and 85 percent and a lifetime risk of ovarian cancer of between 15 and 40 percent. Some mutations associated with cancer, such as p53, BRCA1 and BRCA2, occur in mechanisms to correct errors in DNA. These mutations are either inherited or acquired after birth. Presumably, they allow further mutations, which allow uncontrolled division, lack of attachment, and metastasis to distant organs.[50][70] However, there is strong evidence of residual risk variation that goes well beyond hereditary BRCA gene mutations between carrier families. This is caused by unobserved risk factors.[71]This implicates environmental and other causes as triggers for breast cancers. The inherited mutation in BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes can interfere with repair of DNA cross links and DNA double strand breaks (known functions of the encoded protein).[72] These carcinogens cause DNA damage such as DNA cross links and double strand breaks that often require repairs by pathways containing BRCA1 and BRCA2.[73][74] However, mutations in BRCA genes account for only 2 to 3 percent of all breast cancers.[75] Levin et al. say that cancer may not be inevitable for all carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2mutations.[76] About half of hereditary breast–ovarian cancer syndromes involve unknown genes.

GATA-3 directly controls the expression of estrogen receptor (ER) and other genes associated with epithelial differentiation, and the loss of GATA-3 leads to loss of differentiation and poor prognosis due to cancer cell invasion and metastasis.[77]

Diagnosis

Early signs of possible breast cancer Most types of breast cancer are easy to diagnose by microscopic analysis of a sample—or biopsy—of the affected area of the breast. Also, there are types of breast cancer that require specialized lab exams.

The two most commonly used screening methods, physical examination of the breasts by a healthcare provider and mammography, can offer an approximate likelihood that a lump is cancer, and may also detect some other lesions, such as a simple cyst.[78] When these examinations are inconclusive, a healthcare provider can remove a sample of the fluid in the lump for microscopic analysis (a procedure known as fine needle aspiration, or fine needle aspiration and cytology—FNAC) to help establish the diagnosis. The needle aspiration may be performed in a healthcare provider's office or clinic using local anaesthetic if required.[clarification needed] A finding of clear fluid makes the lump highly unlikely to be cancerous, but bloody fluid may be sent off for inspection under a microscope for cancerous cells. Together, physical examination of the breasts, mammography, and FNAC can be used to diagnose breast cancer with a good degree of accuracy.

Other options for biopsy include a core biopsy or vacuum-assisted breast biopsy,[79] which are procedures in which a section of the breast lump is removed; or anexcisional biopsy, in which the entire lump is removed. Very often the results of physical examination by a healthcare provider, mammography, and additional tests that may be performed in special circumstances (such as imaging by ultrasound or MRI) are sufficient to warrant excisional biopsy as the definitive diagnostic and primary treatment method.

Excised human breasttissue, showing an irregular, dense, whitestellate area of cancer2 cm in diameter, within yellow fatty tissue.

High-grade invasive ductal carcinoma, with minimal tubule formation, markedpleomorphism, and prominent mitoses, 40x field.

Micrograph showing a lymph node invaded by ductal breast carcinoma, with extension of the tumour beyond the lymph node.

Neuropilin-2 expression in normal breast and breast carcinoma tissue.

F-18 FDG PET/CT: A breast cancer metastasis to the right scapula

Elastography shows stiff cancer tisuue on ultrasound imaging.

Ultrasound image shows irregular shaped mass of breast cancer.

Classification

Breast cancers are classified by several grading systems. Each of these influences the prognosis and can affect treatment response. Description of a breast cancer optimally includes all of these factors.

- Histopathology. Breast cancer is usually classified primarily by its histological appearance. Most breast cancers are derived from the epithelium lining the ducts or lobules, and these cancers are classified as ductal or lobular carcinoma. Carcinoma in situ is growth of low grade cancerous or precancerous cells within a particular tissue compartment such as the mammary duct without invasion of the surrounding tissue. In contrast, invasive carcinoma does not confine itself to the initial tissue compartment.[80]

- Grade. Grading compares the appearance of the breast cancer cells to the appearance of normal breast tissue. Normal cells in an organ like the breast become differentiated, meaning that they take on specific shapes and forms that reflect their function as part of that organ. Cancerous cells lose that differentiation. In cancer, the cells that would normally line up in an orderly way to make up the milk ducts become disorganized. Cell division becomes uncontrolled. Cell nuclei become less uniform. Pathologists describe cells as well differentiated (low grade), moderately differentiated (intermediate grade), and poorly differentiated (high grade) as the cells progressively lose the features seen in normal breast cells. Poorly differentiated cancers (the ones whose tissue is least like normal breast tissue) have a worse prognosis.

- Stage. Breast cancer staging using the TNM system is based on the size of the tumor (T), whether or not the tumor has spread to the lymph nodes (N) in the armpits, and whether the tumor hasmetastasized (M) (i.e. spread to a more distant part of the body). Larger size, nodal spread, and metastasis have a larger stage number and a worse prognosis.

The main stages are:

- Where available, imaging studies may be employed as part of the staging process in select cases to look for signs of metastatic cancer. However, in cases of breast cancer with low risk for metastasis, the risks associated with PET scans, CT scans, or bone scans outweigh the possible benefits, as these procedures expose the patient to a substantial amount of potentially dangerous ionizing radiation.[81][82]

- Receptor status. Breast cancer cells have receptors on their surface and in their cytoplasm and nucleus. Chemical messengers such as hormones bind to receptors, and this causes changes in the cell. Breast cancer cells may or may not have three important receptors: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2.

ER+ cancer cells (that is, cancer cells that have estrogen receptors) depend on estrogen for their growth, so they can be treated with drugs to block estrogen effects (e.g. tamoxifen), and generally have a better prognosis. Untreated, HER2+ breast cancers are generally more aggressive than HER2- breast cancers,[83][84] but HER2+ cancer cells respond to drugs such as the monoclonal antibodytrastuzumab (in combination with conventional chemotherapy), and this has improved the prognosis significantly.[85] Cells that do not have any of these three receptor types (estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, or HER2) are called triple-negative, although they frequently do express receptors for other hormones, such as androgen receptor and prolactin receptor. - DNA assays. DNA testing of various types including DNA microarrays have compared normal cells to breast cancer cells. The specific changes in a particular breast cancer can be used to classify the cancer in several ways, and may assist in choosing the most effective treatment for that DNA type.

What is breast cancer?

Cancer starts when cells begin to grow out of control. Cells in nearly any part of the body can become cancer, and can spread to other areas of the body. To learn more about how all cancers start and spread, see What Is Cancer?

Breast cancer is a malignant tumor that starts in the cells of the breast. A malignant tumor is a group of cancer cells that can grow into (invade) surrounding tissues or spread (metastasize) to distant areas of the body. The disease occurs almost entirely in women, but men can get it, too.

This information refers only to breast cancer in women. For information on breast cancer in men, seeBreast Cancer in Men.

The normal breast

To understand breast cancer, it helps to have some basic knowledge about the normal structure of the breasts, shown in the diagram below.

The female breast is made up mainly of lobules (milk-producing glands), ducts (tiny tubes that carry the milk from the lobules to the nipple), and stroma (fatty tissue and connective tissue surrounding the ducts and lobules, blood vessels, and lymphatic vessels).

Most breast cancers begin in the cells that line the ducts (ductal cancers). Some begin in the cells that line the lobules (lobular cancers), while a small number start in other tissues.

The lymph (lymphatic) system of the breast

The lymph system is important to understand because it is one way breast cancers can spread. This system has several parts.

Lymph nodes are small, bean-shaped collections of immune system cells (cells that are important in fighting infections) that are connected by lymphatic vessels. Lymphatic vessels are like small veins, except that they carry a clear fluid called lymph (instead of blood) away from the breast. Lymph contains tissue fluid and waste products, as well as immune system cells. Breast cancer cells can enter lymphatic vessels and begin to grow in lymph nodes.

Most lymphatic vessels in the breast connect to lymph nodes under the arm (axillary nodes). Some lymphatic vessels connect to lymph nodes inside the chest (internal mammary nodes) and either above or below the collarbone (supraclavicular or infraclavicular nodes).

If the cancer cells have spread to lymph nodes, there is a higher chance that the cells could have also gotten into the bloodstream and spread (metastasized) to other sites in the body. The more lymph nodes with breast cancer cells, the more likely it is that the cancer may be found in other organs as well. Because of this, finding cancer in one or more lymph nodes often affects the treatment plan. Still, not all women with cancer cells in their lymph nodes develop metastases, and some women can have no cancer cells in their lymph nodes and later develop metastases.

Benign breast lumps

Most breast lumps are not cancerous (benign). Still, some may need to be biopsied (sampled and viewed under a microscope) to prove they are not cancer.

Fibrosis and cysts

Most lumps turn out to be caused by fibrosis and/or cysts, benign changes in the breast tissue that happen in many women at some time in their lives. (This is sometimes called fibrocystic changes and used to be called fibrocystic disease.) Fibrosis is the formation of scar-like (fibrous) tissue, and cysts are fluid-filled sacs. These conditions are most often diagnosed by a doctor based on symptoms, such as breast lumps, swelling, and tenderness or pain. These symptoms tend to be worse just before a woman's menstrual period is about to begin. Her breasts may feel lumpy and, sometimes, she may notice a clear or slightly cloudy nipple discharge.

Fibroadenomas and intraductal papillomas

Benign breast tumors such as fibroadenomas or intraductal papillomas are abnormal growths, but they are not cancerous and do not spread outside the breast to other organs. They are not life threatening.

What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease, such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. For example, exposing skin to strong sunlight is a risk factor for skin cancer. Smoking is a risk factor for cancers of the lung, mouth, larynx (voice box), bladder, kidney, and several other organs.

But risk factors don't tell us everything. Having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that you will get the disease. Most women who have one or more breast cancer risk factors never develop the disease, while many women with breast cancer have no apparent risk factors (other than being a woman and growing older). Even when a woman with risk factors develops breast cancer, it is hard to know just how much these factors might have contributed.

Some risk factors, like a person's age or race, can't be changed. Others are linked to cancer-causing factors in the environment. Still others are related to personal behaviors, such as smoking, drinking, and diet. Some factors influence risk more than others, and your risk for breast cancer can change over time, due to factors such as aging or lifestyle.

Risk factors not related to personal choice

Gender

Simply being a woman is the main risk factor for developing breast cancer. Men can develop breast cancer, but this disease is about 100 times more common among women than men. This is probably because men have less of the female hormones estrogen and progesterone, which can promote breast cancer cell growth

Aging

Your risk of developing breast cancer increases as you get older. About 1 out of 8 invasive breast cancers are found in women younger than 45, while about 2 of 3 invasive breast cancers are found in women age 55 or older.

Genetic risk factors

About 5% to 10% of breast cancer cases are thought to be hereditary, meaning that they result directly from gene defects (called mutations) inherited from a parent. See "Do we know what causes breast cancer?" for more information about genes and DNA and how they can affect breast cancer risk.

BRCA1 and BRCA2: The most common cause of hereditary breast cancer is an inherited mutation in the BRCA1 andBRCA2 genes. In normal cells, these genes help prevent cancer by making proteins that keep the cells from growing abnormally. If you have inherited a mutated copy of either gene from a parent, you have a high risk of developing breast cancer during your lifetime.

Although in some families with BRCA1 mutations the lifetime risk of breast cancer is as high as 80%, on average this risk seems to be in the range of 55 to 65%. For BRCA2 mutations the risk is lower, around 45%.

Breast cancers linked to these mutations occur more often in younger women and more often affect both breasts than cancers not linked to these mutations. Women with these inherited mutations also have an increased risk for developing other cancers, particularly ovarian cancer.

In the United States BRCA mutations are more common in Jewish people of Ashkenazi (Eastern Europe) origin than in other racial and ethnic groups, but they can occur in anyone.

Changes in other genes: Other gene mutations can also lead to inherited breast cancers. These gene mutations are much rarer and often do not increase the risk of breast cancer as much as the BRCA genes. They are not frequent causes of inherited breast cancer.

- ATM: The ATM gene normally helps repair damaged DNA. Inheriting 2 abnormal copies of this gene causes the disease ataxia-telangiectasia. Inheriting 1 mutated copy of this gene has been linked to a high rate of breast cancer in some families.

- TP53: The TP53 gene gives instructions for making a protein called p53 that helps stop the growth of abnormal cells. Inherited mutations of this gene cause Li-Fraumeni syndrome (named after the 2 researchers who first described it). People with this syndrome have an increased risk of developing breast cancer, as well as several other cancers such as leukemia, brain tumors, and sarcomas (cancer of bones or connective tissue). This is a rare cause of breast cancer.

- CHEK2: The Li-Fraumeni syndrome can also be caused by inherited mutations in the CHEK2 gene. Even when it does not cause this syndrome, it can increase breast cancer risk about twofold when it is mutated.

- PTEN: The PTEN gene normally helps regulate cell growth. Inherited mutations in this gene can cause Cowden syndrome, a rare disorder in which people are at increased risk for both benign and malignant breast tumors, as well as growths in the digestive tract, thyroid, uterus, and ovaries. Defects in this gene can also cause a different syndrome called Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome that is not thought to be linked to breast cancer risk. Recently, the syndromes caused by PTEN have been combined into one called PTEN Tumor Hamartoma Syndrome.

- CDH1: Inherited mutations in this gene cause hereditary diffuse gastric cancer, a syndrome in which people develop a rare type of stomach cancer at an early age. Women with mutations in this gene also have an increased risk of invasive lobular breast cancer.

- STK11: Defects in this gene can lead to Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. People with this disorder develop pigmented spots on their lips and in their mouths, polyps in the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts, and have an increased risk of many types of cancer, including breast cancer.

- PALB2: The PALB2 gene makes a protein that interacts with the protein made by the BRCA2 gene. Defects (mutations) in this gene can lead to an increased risk of breast cancer. It isn’t yet clear if PALB2 gene mutations also increase the risk for ovarian cancer and male breast cancer.

Genetic testing: Genetic tests can be done to look for mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes (or some other genes linked to breast cancer risk). Although testing may be helpful in some situations, the pros and cons need to be considered carefully. For more information, see "Can breast cancer be prevented?"

Family history of breast cancer

Breast cancer risk is higher among women whose close blood relatives have this disease.

Having one first-degree relative (mother, sister, or daughter) with breast cancer approximately doubles a woman's risk. Having 2 first-degree relatives increases her risk about 3-fold.

The exact risk is not known, but women with a family history of breast cancer in a father or brother also have an increased risk of breast cancer. Altogether, less than 15% of women with breast cancer have a family member with this disease. This means that most (over 85%) women who get breast cancer do not have a family history of this disease.

Personal history of breast cancer

A woman with cancer in one breast has an increased risk of developing a new cancer in the other breast or in another part of the same breast. (This is different from a recurrence (return) of the first cancer.) This risk is even higher if breast cancer was diagnosed at a younger age.

Race and ethnicity

Overall, white women are slightly more likely to develop breast cancer than are African-American women, but African-American women are more likely to die of this cancer. However, in women under 45 years of age, breast cancer is more common in African- American women. Asian, Hispanic, and Native-American women have a lower risk of developing and dying from breast cancer.

Dense breast tissue

Breasts are made up of fatty tissue, fibrous tissue, and glandular tissue. Someone is said to have dense breast tissue (as seen on a mammogram) when they have more glandular and fibrous tissue and less fatty tissue. Women withdense breasts on mammogram have a risk of breast cancer that is 1.2 to 2 times that of women with average breast density. Dense breast tissue can also make mammograms less accurate.

A number of factors can affect breast density, such as age, menopausal status, certain medications (including menopausal hormone therapy), pregnancy, and genetics.

Certain benign breast conditions

Women diagnosed with certain benign breast conditions might have an increased risk of breast cancer. Some of these conditions are more closely linked to breast cancer risk than others. Doctors often divide benign breast conditions into 3 general groups, depending on how they affect this risk.

Non-proliferative lesions: These conditions are not associated with overgrowth of breast tissue. They do not seem to affect breast cancer risk, or if they do, it is to a very small extent. They include:

- Fibrosis and/or simple cysts (this used to be called fibrocystic disease or changes)

- Mild hyperplasia

- Adenosis (non-sclerosing)

- Ductal ectasia

- Phyllodes tumor (benign)

- A single papilloma

- Fat necrosis

- Periductal fibrosis

- Squamous and apocrine metaplasia

- Epithelial-related calcifications

- Other benign tumors (lipoma, hamartoma, hemangioma, neurofibroma, adenomyoepthelioma)

Mastitis (infection of the breast) is not a lesion, but is a condition that can occur that does not increase the risk of breast cancer.

Proliferative lesions without atypia: These conditions show excessive growth of cells in the ducts or lobules of the breast tissue. They seem to raise a woman's risk of breast cancer slightly (1½ to 2 times normal). They include:

- Usual ductal hyperplasia (without atypia)

- Fibroadenoma

- Sclerosing adenosis

- Several papillomas (called papillomatosis)

- Radial scar

Proliferative lesions with atypia: In these conditions, there is an overgrowth of cells in the ducts or lobules of the breast tissue, with some of the cells no longer appearing normal. They have a stronger effect on breast cancer risk, raising it 3½ to 5 times higher than normal. These types of lesions include:

- Atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH)

- Atypical lobular hyperplasia (ALH)

Women with a family history of breast cancer and either hyperplasia or atypical hyperplasia have an even higher risk of developing a breast cancer.

Lobular carcinoma in situ

In lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) cells that look like cancer cells are growing in the lobules of the milk-producing glands of the breast, but they do not grow through the wall of the lobules. LCIS (also called lobular neoplasia) is sometimes grouped with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) as a non-invasive breast cancer, but it differs from DCIS in that it doesn’t seem to become an invasive cancer if it isn’t treated.

Women with this condition have a 7- to 11-fold increased risk of developing invasive cancer in either breast. For this reason, women with LCIS should make sure they have regular mammograms and doctor visits.

Menstrual periods

Women who have had more menstrual cycles because they started menstruating early (before age 12) and/or went through menopause later (after age 55) have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer. The increase in risk may be due to a longer lifetime exposure to the hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Previous chest radiation

Women who, as children or young adults, had radiation therapy to the chest area as treatment for another cancer(such as lymphoma) have a significantly increased risk for breast cancer. This varies with the patient's age when they had radiation. If chemotherapy was also given, it may have stopped ovarian hormone production for some time, lowering the risk. The risk of developing breast cancer from chest radiation is highest if the radiation was given during adolescence, when the breasts were still developing. Radiation treatment after age 40 does not seem to increase breast cancer risk.

Diethylstilbestrol exposure

From the 1940s through the 1960s some pregnant women were given the drug diethylstilbestrol (DES) because it was thought to lower their chances of miscarriage (losing the baby). These women have a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer. Women whose mothers took DES during pregnancy may also have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer. For more information on DES, see DES Exposure: Questions and Answers.

Lifestyle-related factors and breast cancer risk

Having children

Women who have had no children or who had their first child after age 30 have a slightly higher breast cancer risk overall. Having many pregnancies and becoming pregnant at a young age reduce breast cancer risk overall. Still, the effect of pregnancy is different for different types of breast cancer. For a certain type of breast cancer known as triple-negative, pregnancy seems to increase risk.

Birth control

Oral contraceptives: Studies have found that women using oral contraceptives (birth control pills) have a slightly greater risk of breast cancer than women who have never used them. This risk seems to go back to normal over time once the pills are stopped. Women who stopped using oral contraceptives more than 10 years ago do not appear to have any increased breast cancer risk. When thinking about using oral contraceptives, women should discuss their other risk factors for breast cancer with their health care team.

Depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA; Depo-Provera®) is an injectable form of progesterone that is given once every 3 months as birth control. A few studies have looked at the effect of DMPA on breast cancer risk. Women currently using DMPA seem to have an increase in risk, but the risk doesn’t seem to be increased if this drug was used more than 5 years ago.

Hormone therapy after menopause

Hormone therapy with estrogen (often combined with progesterone) has been used for many years to help relieve symptoms of menopause and to help prevent osteoporosis (thinning of the bones). Earlier studies suggested it might have other health benefits as well, but these benefits have not been found in more recent, better designed studies. This treatment goes by many names, such as post-menopausal hormone therapy (PHT), hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and menopausal hormone therapy (MHT).

There are 2 main types of hormone therapy. For women who still have a uterus (womb), doctors generally prescribe both estrogen and progesterone (known as combined hormone therapy or HT). Progesterone is needed because estrogen alone can increase the risk of cancer of the uterus. For women who no longer have a uterus (those who've had a hysterectomy), estrogen alone can be prescribed. This is commonly known as estrogen replacement therapy(ERT) or just estrogen therapy (ET).

Studies have shown that using combined hormone therapy after menopause increases the risk of getting breast cancer. It may also increase the chances of dying from breast cancer.

The use of estrogen alone after menopause does not appear to increase the risk of developing breast cancer.

For more information about this topic, see Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Cancer Risk.

Breastfeeding

Some studies suggest that breastfeeding may slightly lower breast cancer risk, especially if it is continued for 1½ to 2 years. But this has been a difficult area to study, especially in countries such as the United States, where breastfeeding for this long is uncommon.

One explanation for this possible effect may be that breastfeeding reduces a woman's total number of lifetime menstrual cycles (similar to starting menstrual periods at a later age or going through early menopause).

Drinking alcohol

The use of alcohol is clearly linked to an increased risk of developing breast cancer. The risk increases with the amount of alcohol consumed. Compared with non-drinkers, women who consume 1 alcoholic drink a day have a very small increase in risk. Those who have 2 to 5 drinks daily have about 1½ times the risk of women who don’t drink alcohol. Excessive alcohol consumption is also known to increase the risk of developing several other types of cancer.

Being overweight or obese

Being overweight or obese after menopause increases breast cancer risk. Before menopause your ovaries produce most of your estrogen, and fat tissue produces a small amount of estrogen. After menopause (when the ovaries stop making estrogen), most of a woman's estrogen comes from fat tissue. Having more fat tissue after menopause can increase your chance of getting breast cancer by raising estrogen levels. Also, women who are overweight tend to have higher blood insulin levels. Higher insulin levels have also been linked to some cancers, including breast cancer.

But the connection between weight and breast cancer risk is complex. For example, the risk appears to be increased for women who gained weight as an adult but may not be increased among those who have been overweight since childhood. Also, excess fat in the waist area may affect risk more than the same amount of fat in the hips and thighs. Researchers believe that fat cells in various parts of the body have subtle differences that may explain this.

Physical activity

Evidence is growing that physical activity in the form of exercise reduces breast cancer risk. The main question is how much exercise is needed. In one study from the Women's Health Initiative, as little as 1.25 to 2.5 hours per week of brisk walking reduced a woman's risk by 18%. Walking 10 hours a week reduced the risk a little more.

Unclear factors

Diet and vitamin intake

Many studies have looked for a link between what women eat and breast cancer risk, but so far the results have been conflicting. Some studies have indicated that diet may play a role, while others found no evidence that diet influences breast cancer risk. For example, a recent study found a higher risk of breast cancer in women who ate more red meat.

Studies have also looked at vitamin levels, again with inconsistent results. Some studies actually found an increased risk of breast cancer in women with higher levels of certain nutrients. So far, no study has shown that taking vitamins reduces breast cancer risk. This is not to say that there is no point in eating a healthy diet. A diet low in fat, low in red meat and processed meat, and high in fruits and vegetables might have other health benefits.

Most studies have found that breast cancer is less common in countries where the typical diet is low in total fat, low in polyunsaturated fat, and low in saturated fat. But many studies of women in the United States have not linked breast cancer risk to dietary fat intake. Researchers are still not sure how to explain this apparent disagreement. It may be at least partly due to the effect of diet on body weight (see below). Also, studies comparing diet and breast cancer risk in different countries are complicated by other differences (like activity level, intake of other nutrients, and genetic factors) that might also affect breast cancer risk.

More research is needed to understand the effect of the types of fat eaten on breast cancer risk. But it is clear that calories do count, and fat is a major source of calories. High-fat diets can lead to being overweight or obese, which is a breast cancer risk factor. A diet high in fat has also been shown to influence the risk of developing several other types of cancer, and intake of certain types of fat is clearly related to heart disease risk.

Chemicals in the environment

A great deal of research has been reported and more is being done to understand possible environmental influences on breast cancer risk.

Compounds in the environment that have estrogen-like properties are of special interest. For example, substances found in some plastics, certain cosmetics and personal care products, pesticides (such as DDE), and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) seem to have such properties. These could in theory affect breast cancer risk.

This issue understandably invokes a great deal of public concern, but at this time research does not show a clear link between breast cancer risk and exposure to these substances. Unfortunately, studying such effects in humans is difficult. More research is needed to better define the possible health effects of these and similar substances.

Tobacco smoke

For a long time, studies found no link between cigarette smoking and breast cancer. In recent years though, more studies have found that long-term heavy smoking is linked to a higher risk of breast cancer. Some studies have found that the risk is highest in certain groups, such as women who started smoking before they had their first child. The 2014 US Surgeon General’s report on smoking concluded that there is “suggestive but not sufficient” evidence that smoking increases the risk of breast cancer.

An active focus of research is whether secondhand smoke increases the risk of breast cancer. Both mainstream and secondhand smoke contain chemicals that, in high concentrations, cause breast cancer in rodents. Chemicals in tobacco smoke reach breast tissue and are found in breast milk.

The evidence on secondhand smoke and breast cancer risk in human studies is controversial, at least in part because the link between smoking and breast cancer hasn’t been clear. One possible explanation for this is that tobacco smoke may have different effects on breast cancer risk in smokers and in those who are just exposed to smoke.