Signs and symptoms

Outcomes of poliovirus infection| Outcome | Proportion of cases[1] |

|---|

| No symptoms | 72% |

| Minor illness | 24% |

Nonparalytic aseptic

meningitis | 1–5% |

| Paralytic poliomyelitis | 0.1–0.5% |

| — Spinal polio | 79% of paralytic cases |

| — Bulbospinal polio | 19% of paralytic cases |

| — Bulbar polio | 2% of paralytic cases |

The term "poliomyelitis" is used to identify the disease caused by any of the three serotypes of poliovirus. Two basic patterns of polio infection are described: a minor illness which does not involve the central nervous system (CNS), sometimes called abortive poliomyelitis, and a major illness involving the CNS, which may be paralytic or nonparalytic.[12] In most people with a normal immune system, a poliovirus infection is asymptomatic. Rarely, the infection produces minor symptoms; these may include upper respiratory tract infection (sore throat and fever), gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation or, rarely, diarrhea), and influenza-like illness.[1]

The virus enters the central nervous system in about 1% of infections. Most patients with CNS involvement develop nonparalytic aseptic meningitis, with symptoms of headache, neck, back, abdominal and extremity pain, fever, vomiting, lethargy, and irritability.[13][14] About one to five in 1000 cases progress toparalytic disease, in which the muscles become weak, floppy and poorly controlled, and, finally, completely paralyzed; this condition is known as acute flaccid paralysis.[15] Depending on the site of paralysis, paralytic poliomyelitis is classified as spinal, bulbar, or bulbospinal. Encephalitis, an infection of the brain tissue itself, can occur in rare cases, and is usually restricted to infants. It is characterized by confusion, changes in mental status, headaches, fever, and, less commonly, seizures and spastic paralysis.[16]

Cause

Poliomyelitis is caused by infection with a member of the genus Enterovirus known as poliovirus (PV). This group of RNA viruses colonize the gastrointestinal tract[17] — specifically the oropharynx and the intestine. The incubation time (to the first signs and symptoms) ranges from three to 35 days, with a more common span of six to 20 days.[1] PV infects and causes disease in humans alone.[18] Its structure is very simple, composed of a single (+) sense RNA genome enclosed in a protein shell called a capsid.[18] In addition to protecting the virus’s genetic material, the capsid proteins enable poliovirus to infect certain types of cells. Threeserotypes of poliovirus have been identified—poliovirus type 1 (PV1), type 2 (PV2), and type 3 (PV3)—each with a slightly different capsid protein.[19] All three are extremely virulent and produce the same disease symptoms.[18] PV1 is the most commonly encountered form, and the one most closely associated with paralysis.[20]

Individuals who are exposed to the virus, either through infection or by immunization with polio vaccine, develop immunity. In immune individuals, IgA antibodiesagainst poliovirus are present in the tonsils and gastrointestinal tract, and are able to block virus replication; IgG and IgM antibodies against PV can prevent the spread of the virus to motor neurons of the central nervous system.[21] Infection or vaccination with one serotype of poliovirus does not provide immunity against the other serotypes, and full immunity requires exposure to each serotype.[21]

A rare condition with a similar presentation, nonpoliovirus poliomyelitis, may result from infections with nonpoliovirus enteroviruses.[22]

Transmission

Poliomyelitis is highly contagious via the fecal-oral (intestinal source) and the oral-oral (oropharyngeal source) routes.[21] In endemic areas, wild polioviruses can infect virtually the entire human population.[23] It is seasonal in temperate climates, with peak transmission occurring in summer and autumn.[21] These seasonal differences are far less pronounced in tropical areas.[23] The time between first exposure and first symptoms, known as the incubation period, is usually 6 to 20 days, with a maximum range of three to 35 days.[24] Virus particles are excreted in the feces for several weeks following initial infection.[24] The disease is transmitted primarily via the fecal-oral route, by ingesting contaminated food or water. It is occasionally transmitted via the oral-oral route,[20] a mode especially visible in areas with good sanitation and hygiene.[21] Polio is most infectious between seven and 10 days before and after the appearance of symptoms, but transmission is possible as long as the virus remains in the saliva or feces.[20]

Factors that increase the risk of polio infection or affect the severity of the disease include immune deficiency,[25] malnutrition,[26] physical activity immediately following the onset of paralysis,[27]skeletal muscle injury due to injection of vaccines or therapeutic agents,[28] and pregnancy.[29] Although the virus can cross the maternal-fetal barrier during pregnancy, the fetus does not appear to be affected by either maternal infection or polio vaccination.[30] Maternal antibodies also cross the placenta, providing passive immunity that protects the infant from polio infection during the first few months of life.[31]

As a precaution against infection, public swimming pools were often closed in affected areas during poliomyelitis epidemics.

Pathophysiology

A blockage of the lumbar anterior spinal cord artery due to polio (PV3) Poliovirus enters the body through the mouth, infecting the first cells with which it comes in contact — the pharynx and intestinal mucosa. It gains entry by binding to an immunoglobulin-like receptor, known as the poliovirus receptor or CD155, on the cell membrane.[32] The virus then hijacks the host cell's own machinery, and begins to replicate. Poliovirus divides within gastrointestinal cells for about a week, from where it spreads to the tonsils (specifically the follicular dendritic cellsresiding within the tonsilar germinal centers), the intestinal lymphoid tissue including the M cells of Peyer's patches, and the deep cervical and mesenteric lymph nodes, where it multiplies abundantly. The virus is subsequently absorbed into the bloodstream.[33]

Known as viremia, the presence of virus in the bloodstream enables it to be widely distributed throughout the body. Poliovirus can survive and multiply within the blood and lymphatics for long periods of time, sometimes as long as 17 weeks.[34] In a small percentage of cases, it can spread and replicate in other sites, such asbrown fat, the reticuloendothelial tissues, and muscle.[35] This sustained replication causes a major viremia, and leads to the development of minor influenza-like symptoms. Rarely, this may progress and the virus may invade the central nervous system, provoking a local inflammatory response. In most cases, this causes a self-limiting inflammation of the meninges, the layers of tissue surrounding the brain, which is known as nonparalytic aseptic meningitis.[13] Penetration of the CNS provides no known benefit to the virus, and is quite possibly an incidental deviation of a normal gastrointestinal infection.[36] The mechanisms by which poliovirus spreads to the CNS are poorly understood, but it appears to be primarily a chance event—largely independent of the age, gender, or socioeconomic position of the individual.[36]

Paralytic polio

Denervation of skeletal muscle tissue secondary to poliovirus infection can lead to paralysis. In around 1% of infections, poliovirus spreads along certain nerve fiber pathways, preferentially replicating in and destroying motor neurons within the spinal cord,brain stem, or motor cortex. This leads to the development of paralytic poliomyelitis, the various forms of which (spinal, bulbar, and bulbospinal) vary only with the amount of neuronal damage and inflammation that occurs, and the region of the CNS affected.

The destruction of neuronal cells produces lesions within the spinal ganglia; these may also occur in the reticular formation, vestibular nuclei, cerebellar vermis, and deep cerebellar nuclei.[36] Inflammation associated with nerve cell destruction often alters the color and appearance of the gray matter in the spinal column, causing it to appear reddish and swollen.[13] Other destructive changes associated with paralytic disease occur in the forebrain region, specifically the hypothalamus andthalamus.[36] The molecular mechanisms by which poliovirus causes paralytic disease are poorly understood.

Early symptoms of paralytic polio include high fever, headache, stiffness in the back and neck, asymmetrical weakness of various muscles, sensitivity to touch,difficulty swallowing, muscle pain, loss of superficial and deep reflexes, paresthesia (pins and needles), irritability, constipation, or difficulty urinating. Paralysis generally develops one to ten days after early symptoms begin, progresses for two to three days, and is usually complete by the time the fever breaks.[37]

The likelihood of developing paralytic polio increases with age, as does the extent of paralysis. In children, nonparalytic meningitis is the most likely consequence of CNS involvement, and paralysis occurs in only one in 1000 cases. In adults, paralysis occurs in one in 75 cases.[38] In children under five years of age, paralysis of one leg is most common; in adults, extensive paralysis of the chest and abdomen also affecting all four limbs—quadriplegia—is more likely.[39] Paralysis rates also vary depending on the serotype of the infecting poliovirus; the highest rates of paralysis (one in 200) are associated with poliovirus type 1, the lowest rates (one in 2,000) are associated with type 2.[40]

Spinal polio

Spinal polio, the most common form of paralytic poliomyelitis, results from viral invasion of the motor neurons of the anterior horn cells, or the ventral (front) grey matter section in the spinal column, which are responsible for movement of the muscles, including those of the trunk, limbs, and the intercostal muscles.[15] Virus invasion causes inflammation of the nerve cells, leading to damage or destruction of motor neuron ganglia. When spinal neurons die, Wallerian degeneration takes place, leading to weakness of those muscles formerly innervated by the now-dead neurons.[41] With the destruction of nerve cells, the muscles no longer receive signals from the brain or spinal cord; without nerve stimulation, the muscles atrophy, becoming weak, floppy and poorly controlled, and finally completely paralyzed.[15] Maximum paralysis progresses rapidly (two to four days), and usually involves fever and muscle pain. Deep tendon reflexes are also affected, and are typically absent or diminished; sensation (the ability to feel) in the paralyzed limbs, however, is not affected.[42]

The extent of spinal paralysis depends on the region of the cord affected, which may be cervical, thoracic, or lumbar.[43] The virus may affect muscles on both sides of the body, but more often the paralysis is asymmetrical.[33] Any limb or combination of limbs may be affected—one leg, one arm, or both legs and both arms. Paralysis is often more severe proximally (where the limb joins the body) than distally (the fingertips and toes).[33]

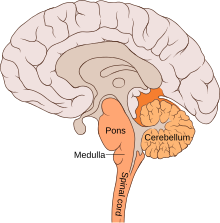

Bulbar polio

The location and anatomy of the bulbar region (in orange) Making up about 2% of cases of paralytic polio, bulbar polio occurs when poliovirus invades and destroys nerves within the bulbar region of the brain stem.[1] The bulbar region is a white matter pathway that connects the cerebral cortex to the brain stem. The destruction of these nerves weakens the muscles supplied by thecranial nerves, producing symptoms of encephalitis, and causes difficulty breathing, speaking and swallowing.[14] Critical nerves affected are the glossopharyngeal nerve (which partially controls swallowing and functions in the throat, tongue movement, and taste), the vagus nerve (which sends signals to the heart, intestines, and lungs), and the accessory nerve (which controls upper neck movement). Due to the effect on swallowing, secretions of mucus may build up in the airway, causing suffocation.[37] Other signs and symptoms include facial weakness (caused by destruction of the trigeminal nerve and facial nerve, which innervate the cheeks, tear ducts, gums, and muscles of the face, among other structures), double vision, difficulty in chewing, and abnormal respiratory rate, depth, and rhythm (which may lead to respiratory arrest). Pulmonary edema and shock are also possible and may be fatal.[43]

Bulbospinal polio

Approximately 19% of all paralytic polio cases have both bulbar and spinal symptoms; this subtype is called respiratory or bulbospinal polio.[1] Here, the virus affects the upper part of the cervical spinal cord (cervical vertebrae C3 through C5), and paralysis of the diaphragm occurs. The critical nerves affected are thephrenic nerve (which drives the diaphragm to inflate the lungs) and those that drive the muscles needed for swallowing. By destroying these nerves, this form of polio affects breathing, making it difficult or impossible for the patient to breathe without the support of a ventilator. It can lead to paralysis of the arms and legs and may also affect swallowing and heart functions.[44]

Diagnosis

Paralytic poliomyelitis may be clinically suspected in individuals experiencing acute onset of flaccid paralysis in one or more limbs with decreased or absent tendon reflexes in the affected limbs that cannot be attributed to another apparent cause, and without sensory or cognitive loss.[45]

A laboratory diagnosis is usually made based on recovery of poliovirus from a stool sample or a swab of the pharynx. Antibodies to poliovirus can be diagnostic, and are generally detected in the blood of infected patients early in the course of infection.[1] Analysis of the patient's cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is collected by a lumbar puncture ("spinal tap"), reveals an increased number of white blood cells (primarily lymphocytes) and a mildly elevated protein level. Detection of virus in the CSF is diagnostic of paralytic polio, but rarely occurs.[1]

If poliovirus is isolated from a patient experiencing acute flaccid paralysis, it is further tested through oligonucleotide mapping (genetic fingerprinting), or more recently by PCR amplification, to determine whether it is "wild type" (that is, the virus encountered in nature) or "vaccine type" (derived from a strain of poliovirus used to produce polio vaccine).[46] It is important to determine the source of the virus because for each reported case of paralytic polio caused by wild poliovirus, an estimated 200 to 3,000 other contagious asymptomatic carriers exist.[47]