Medi Services

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a serious form of pneumonia. It is caused by a virus that was first identified in 2003. Infection with the SARS virus causes acute respiratory distress (severe breathing difficulty) and sometimes death.

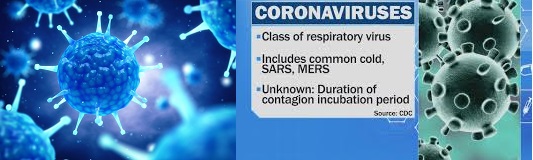

SARS is caused by a member of the coronavirus family of viruses (the same family that can cause the common cold). It is believed the 2003 epidemic started when the virus spread from small mammals in China.

When someone with SARS coughs or sneezes, infected droplets spray into the air. You can catch the SARS virus if you breathe in or touch these particles. The SARS virus may live on hands, tissues, and other surfaces for up to 6 hours in these droplets and up to 3 hours after the droplets have dried.

While the spread of droplets through close contact caused most of the early SARS cases, SARS might also spread by hands and other objects the droplets has touched. Airborne transmission is a real possibility in some cases. Live virus has even been found in the stool of people with SARS, where it has been shown to live for up to 4 days. The virus may be able to live for months or years when the temperature is below freezing.

With other coronaviruses, becoming infected and then getting sick again (re-infection) is common. This may also be the case with SARS.

Symptoms usually occur about 2 to 10 days after coming in contact with the virus. In some cases, SARS started sooner or later after first contact. People with active symptoms of illness are contagious. But it is not known for how long a person may be contagious before or after symptoms appear.

The main symptoms are:

The most common symptoms are:

Less common symptoms include:

In some people, the lung symptoms get worse during the second week of illness, even after the fever has stopped.

Initial symptoms are flu-like and may include fever, myalgia, lethargy symptoms, cough, sore throat, and other nonspecific symptoms. The only symptom common to all patients appears to be a fever above 38 °C (100 °F). SARS may eventually lead to shortness of breath and/orpneumonia; either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia.

SARS may be suspected in a patient who has:

For a case to be considered probable, a chest X-ray must be positive for atypical pneumonia orrespiratory distress syndrome.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has added the category of "laboratory confirmed SARS" for patients who would otherwise be considered "probable" but who have not yet had a positive chest X-ray changes, but have tested positive for SARS based on one of the approved tests (ELISA, immunofluorescence or PCR).[4]

When it comes to the chest X-ray the appearance of SARS is not always uniform but generally appears as an abnormality with patchy infiltrates.[5]

There is no vaccine for SARS to date and isolation and quarantine remain the most effective means to prevent the spread of SARS. Other preventative measures include:

People with SARS must be isolated, preferably in negative pressure rooms, with complete barrier nursing precautions taken for any necessary contact with these patients.

Some of the more serious damage caused by SARS may be due to the body's own immune system reacting in what is known as cytokine storm