Medi Services

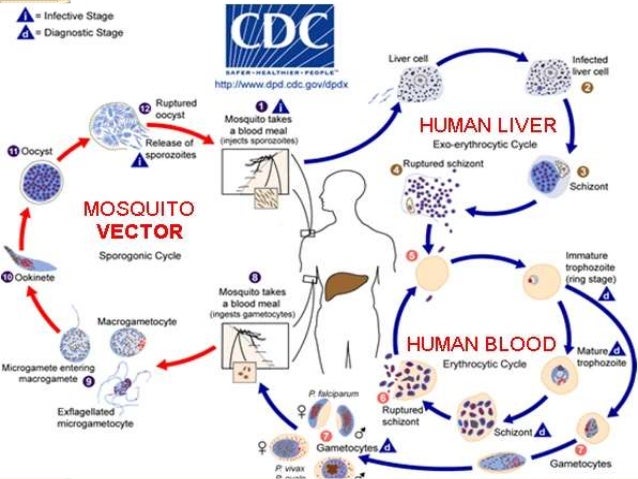

Malaria is a life-threatening blood disease caused by parasites transmitted to humans through the bite of the Anopheles mosquito. Once an infected mosquito bites a human and transmits the parasites, those parasites multiply in the host's liver before infecting and destroying red blood cells.

The disease can be controlled and treated if diagnosed early on. Unfortunately, this is not possible in some areas of the world lacking in medical facilities, where malaria outbreaks can occur.

Researchers are working hard on improving the prevention of malarial infection, early diagnosis and treatment, with just one malaria vaccine close to being licensed so far.

Malaria is caused by the bites from the female Anopheles mosquito, which then infects the body with the parasite Plasmodium. This is the only mosquito that can cause malaria.

The successful development of the parasite within the mosquito depends on several factors, the most important being humidity and ambient temperatures.

When an infected mosquito bites a human host, the parasite enters the bloodstream and lays dormant within the liver. For the next 5-16 days, the host will show no symptoms but the malaria parasite will begin multiplying asexually.7

The new malaria parasites are then released back into the bloodstream when they infect red blood cells and again begin to multiply. Some malaria parasites, however, remain in the liver and are not released until later, resulting in recurrence.

E

E

very year, more than 125 million people visit over 100 countries endemic for malaria. Each year up to 30 000 travelers are estimated to contract malaria and late or wrong malaria diagnosis in their home country may make things worse for them. Fever occurring in a traveler within three months of leaving a malaria-endemic area is considered a medical emergency and should be investigated urgently.

As there is no vaccine available for protection against malaria despite decades of research, there is a need for an alternative method that offers a fairly reliable protection against malaria. And as malaria can be severe in the non-immune, all visitors from non-malarious area to a malarious area should be protected. Anti malarial drugs offer protection against clinical attacks of malaria.

The risk of contracting malaria depends on the region visited, the length of stay, time of visit, type of activity, protection against mosquito bites, compliance with chemoprophylaxis etc. Pregnant women, infants and young children and people who have undergone splenectomy should avoid travel to a malarious area as these people are at higher risk of severe malaria. If travel is unavoidable, these people should take strict precautions to avoid mosquito bites and also take adequate chemoprophylaxis without fail.

Chemoprophylaxis:

Use of anti-malarial drugs to prevent the development of malaria is known as chemoprophylaxis.

The choice of chemoprophylaxis varies depending on the species and drug resistance prevalent in a country.

It must be remembered that no chemoprophylaxis regime provides 100% protection. Therefore it is essential to prevent mosquito bites as well as to comply with chemoprophylaxis. A possibility of malaria should be considered if a febrile illness develops after a week of entering a malarious area as well as up to over a year after visiting such an area, although it is more likely within the first 3 months of return.

Other residents of a malarious area are not advised chemoprophylaxis. It should not be prescribed as a remedy to prevent re-infections in an endemic area.

Primary Prophylaxis: Use of antimalaria drugs at recommended dosage, started 2-20 days before departure to a malarious area and continued for the duration of stay and for 1-4 weeks after return.

Terminal Prophylaxis: Terminal prophylaxis is the administration of primaquine for two weeks after returning from travel to tackle the hypnozoites of P. vivax and P. ovale that can cause relapses of malaria. It is indicated only for persons who have had prolonged exposure in malaria-endemic regions, such as expatriates and long-term travelers like missionaries and Peace Corps volunteers. Primaquine is administered after the traveler leaves an endemic area and usually in conjunction with chloroquine during the last 2 weeks of the 4-week period of prophylaxis after exposure in an endemic area has ended.